JYUcite: research metrics by University of Jyväskylä Open Science Centre

Get CPR | What is CPR?

Full story: read the preprint

7-minute story: see the poster video

Short story:

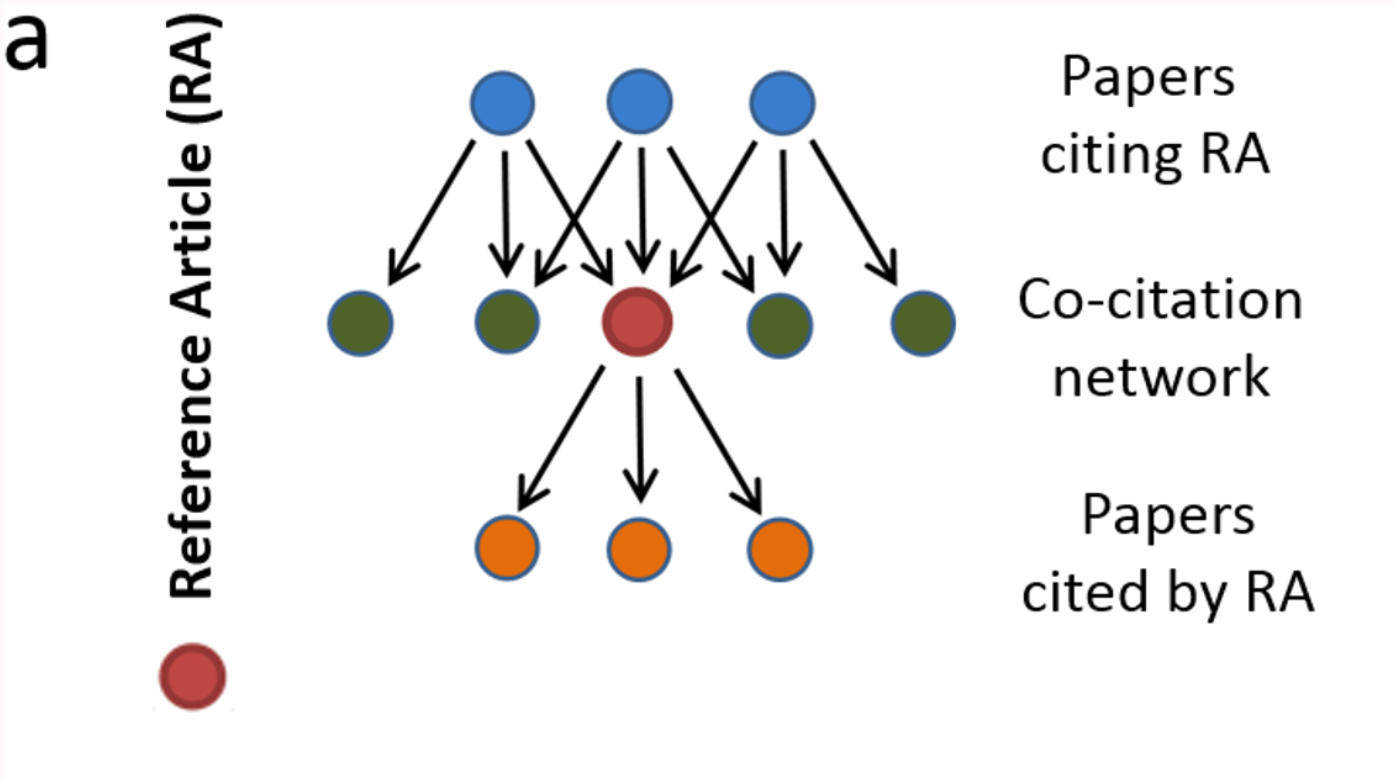

Co-Citation Percentile Rank (CPR) is developed from the basis described by Hutchins et al. The foundational idea - comparing the citation rate of target article to those of 'peer' articles which are cited along the target - makes intuitive sense and allows truly journal-independent research field -normalization for quantitative comparison of academic impact.

Hutchins et al (2016): Fig 1a. Schematic of a co-citation network. The reference article (RA) (red, middle row) cites previous papers from the literature (orange, bottom row); subsequent papers cite the RA (blue, top row). The co-citation network is the set of papers that appear alongside the article in the subsequent citing papers (green, middle row). The field citation rate is calculated as the mean of the latter articles’ journal citation rates.

However, the algorithm by Hutchins et al, called Relative Citation Ratio (RCR) was problematic in several ways (see e.g. Janssens et al)

Most glaring discrepancy to the promise of the idea was that RCR resorted to using Journal Impact Factors (JIF). It calculated the average JIF of journals where the co-cited articles appeared to determine the expected citation rate, to which the target article's rate is then compared. JIF itself is (sort of) an average, from an extremely skewed distribution. Calculation of JIF is a negotiated and extensively gamed process in the publishing industry, and most importantly, it is trivially obvious that neither the true importance nor the citation rates of individual articles are meaningfully correlated with the JIF of the journal where the article appears.

Another shortcoming was the subsequent implementation of RCR in iCite, building the algorithm on top of PubMed citation data. That data is woefully sparse for most fields of science, and fails to capture vast majority of citations. Many articles simply are not indexed by PubMed at all. The sparseness of the citation graph available to Hutchins et al may have been the reason for their choice to resort to JIFs in calculations. Although they state that they chose to use JIF's instead or true article-level citation rates because the latter would be "be highly vulnerable to finite number effects", that is only true for target articles cited only once or twice, or if the citation data one uses is so sparse that meaningful co-citation network sizes are difficult to assemble.

But far more complete citation data coupled with powerful API and search language from Dimensions allows implementing the foundational, pure idea of Hutchins et al. Co-Citation Percentile Rank compares the citation rate (citations / day since work became citable) of an article to the actual citation rates of articles that are co-cited along with that article.

Because distributions of citation rates are highly skewed (very small number of articles get cited extremely often, resulting in long-tailed distributions where averages are far larger than medians, in other words, vast majority of articles in any set fall below average), we do not compare the target article citation rate to the average of the co-citation article set. Instead, we calculate the percentile rank of the target article citation rate in its co-citation article set. Thus, values range from zero to 99th percentile, with larger values indicating more citation impact in the article's own field.

JYUcite allows you to retrieve Co-Citation Percentile Rank for any article that has a DOI and is indexed in the Dimensions database.

What is a good CPR value? What is a poor one? Can you compare CPRs?

More research is needed to answer this with any confidence. Many questions remain. How does CPR relate to other measures of scholarly value of research outputs? To what degree is comparing CPRs really "apples-to-apples" comparison, in relation to field of research, article age, number of authors, etc? Can we interpret CPR differences - after some transformation - on an interval scale (i.e. is 25 → 50 same size difference as 50 → 75)? Or must we limit ourselves to judge CPR differences strictly on an ordinal scale only?

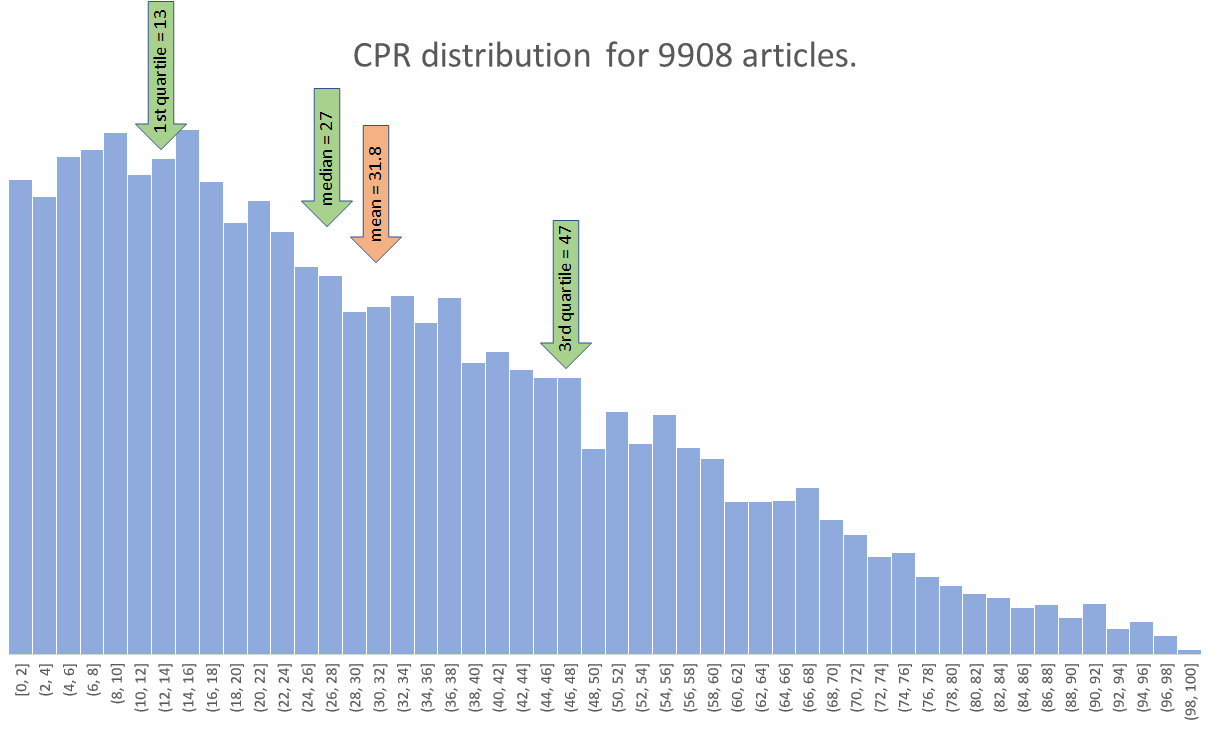

Like most measures involving networks formed by human behaviour, CPR is subject to the friendship paradox: a typical article is more likely to have co-citations that are cited more often than itself, than co-citations that are cited less frequently than itself. This means the distribution of CPR values over a large sample of articles is always right-skewed. Consequently, the perhaps intuitive judgement that CPR = 50 would indicate a mediocre article, is wrong.

Assuming that a sample of 9908 at least three-year-old articles produced by researchers at University of Jyväskylä represents a random sample of research overall (i.e. that research from JYU is not cited differently than research from elsewhere, overall), we could perhaps say - as an early rule-of-thumb - that CPR = 50 and above is firmly in the domain of "very good", CPR = 30 and above is "above mediocre", while CPR = 15 still means "not bad" because more than a quarter of articles score lower than that.